by Shafiya Majid Sharon Mijares, Ph.D.

“I have become an artist in the music of the plants.”

Don Juan Flores Salazar

The Inayati Sufi schools are founded upon the ideal of universality of world religions, following the teachings of Hazrat Inayat Khan, Murshid Samuel Lewis, as well as Rama Krishna, and other teachers, recognizing that the same universal presence is included in all spiritual traditions. This article is intended to add to our knowledge of indigenous traditions as it specifically focuses on the upper Amazonian as well as Kamsá spiritual practices of Sibundoy Valley in Colombia. Many of our newer Latin American initiates have experienced, and continue to experience, some of these healing practices that directly connect participants to the healing power and wisdom of Nature (Mother Earth, Madre Tierra, Pachamama)—directly associated with ingesting plant medicines.

I would like to begin by sharing that I had been part of a Christian mysticism group from the 1970s through the mid to late 80s. By 1989 I had clearly formulated the understanding, both within my mind and heart, that I refused to participate in any organization that failed to recognize the universality of religious and spiritual traditions or that believed itself to be superior to them. Within a short time, a copy of a magazine advertising Omega publications was mailed to me. Hazrat Inayat Khan’s image in the magazine caught my attention. I cut it out and placed in on the refrigerator. One month later I quit my county administrative secretary job to enroll in Matthew Fox’s Institute of Culture and Spirituality (ICCS). I immediately met Saadi Neil Douglas-Klotz. I had been inwardly called, and a new phase in my life had begun!

The education at ICCS emphasized the relationship with the feminine, and with Mother Earth. Twenty-eight years later, I find that my spiritual journey has continued to unfold in this direction. Thus, the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual aspects of my being are both healing and becoming more receptive to the spiritual influences emanating from Nature.

Per the French writer Françoise d'Eaubonne (1974) who coined the term Ecofeminism, the subordination of women and the attempts at subjugating Nature, robbing Mother Earth of her resources, began simultaneously. For example, the transition to a patriarchal ideology

accompanied the acquisition of greater wealth. Developing humanity had discovered the process of “buying and selling,” as agricultural crops exceeded one’s immediate needs (Mijares, Rafea, Falik, & Schipper, 2007). New religious ideologies emerged affirming the ultimate power of the male as well as a male god. They also increasingly favored an unseen god and an afterlife— while diminishing the power and beauty of this one. These religious ideals were filled with beauty, but many wars have been built upon them. The beautiful wisdom and examples emphasized in St. Francis of Assisi’s declaration, that all elements, all creatures, all planetary bodies, and so forth, were our kin, has not created much change.

Each of the world’s religious traditions included some form of the golden rule—a bottom line for ethical living—yet sadly, we have not been able to follow them. Perhaps this is because the imbalances caused by the diminishment of both Women and Nature have prevented grounding of religious messages for the larger masses. It suggests that balancing gender, and reconnecting with Mother Earth, is exactly what is needed at this time.

Beyond affirming the natural beauty and power of the Nature that hosts us, I would like to spend some time highlighting some of Her natural medicines known to the vegetalista and healing traditions practiced in many Latin American nations, and, in particular, the Upper Amazon. The purgas (purges), and the dietas (specific diets) are preparations for taking the master teacher plant, Ayahuasca. Researchers McKenna, Callaway, and Grob (1998) have noted its purpose to be “for curing, for divination, as a diagnostic tool and a magical pipeline to the supernatural realm” (p. 67).

Spiritual Practices in Central and South America

This expands the recognition of spiritual traditions to include those emphasizing plant medicines, especially those of Central and South America, for example, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela. This constitutes a large area of the globe. Few people are aware that many ethnobiologists have been employed (McGrath, 1999; Tindall, 2008) to study and rob the Amazon forest of its medicinal wonders. Many pharmaceutical medicine compounds chemically replicate some of the healing properties, but without the influence of embodied Nature. The medicines lack the spiritual practice and frequencies enabling human beings a way of an intimate relationship with divinity, both within themselves and life.

Amazonian spiritual practice is built upon three practices, including purgas (vomiting up what is detrimental to body and soul), dietas (specific healing diets), and entheogens (for example, Ayahuasca). As an example, I would like to discuss Mayantuyaku, one of the many centers along the Amazon. Numerous people trek through the jungle to participate in healing rituals based on its Ashaninca indigenous tradition. It also exemplifies a similar pattern used in other indigenous groups of the upper Amazon.

Purgas

The master plant teacher, Juan Flores Salazar, offers purgas (purges) regularly. One popular purge is a concentrated tobacco juice. It is believed that tobacco is a master plant that can be used in many ways. A concentrated cup of a strong tobacco decoction is given to each participant. There is a bucket, as well as a liter of fresh water, alongside each person. The process requires drinking the tobacco juice and then following it with cup after cup of water. For instance, two to three plus liters of water will be drunk with the following two hours or more. The bucket is for the purging of toxins. An assistant helps the maestro by refreshing buckets and providing more water as needed. Following the purging, each person will rest. There are other purges prescribed by the curandero, depending upon the person’s health and psychological condition. These purges are especially useful for recovering drug addicts and alcoholics, as well as those with illnesses.

Dietas

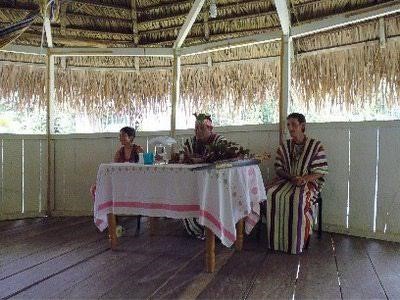

The diet is especially important. Sugar, salt, and spices are limited or not used at all. Although non-fatty fish and chicken may be given, participants primarily eat a bland diet of rice, lentils or peas, eggs, and some vegetables. Boiled rice and green plantains are the primary foods for those on the stricter diet. It is believed that salt encourages one to be more embodied/grounded. Its’ use is restricted to increase participants’ responsiveness to the plant medicines. Diets are significant throughout the Amazonian traditions as a way of preparing for receptivity to another master plant, namely, Ayahuasca.

Plant Medicines

The entheogen most used in ceremony is Ayahuasca. Ayahuasca is often called grandmother, and viewed as feminine (Mijares & Fotiou, 2015). This medicinal remedy is made primarily from the combination of two plants from the Amazonian jungle. One ingredient is the Banisteriopsis cappi vine, considered to be female, and the other is generally the Psychotria, considered to be male (Narby, 1999). These plants are combined, and then cooked in preparation for ceremonial ritual.

A ritual generally begins with the practice of smudging. This is done with incense smoke from Copal resin or Palo Santo (holy stick). Copal has been used throughout Mesoamerica. Palo Santo was primarily used by the Incas, and peoples of the Andes, and has a very pleasant aroma. The curandero blows mapacho smoke (tobacco) into the Ayahuasca brew as icaros/prayers are chanted. Then one by one the participants are given a cup of the medicine. Lights are turned off and silence is kept until the chanting begins. Ceremonies generally begin after 9:00 p.m. and may continue until the morning. Participants can drink again as needed. During that time people are purging as visions and guidance commence. Everyone receives sobladas (a ritual using breath, rose water, and tobacco smoke) toward the end of the ritual at Mayantuyaku. The persons trained in giving sobladas approach as participants sit with palms outstretched as rose water is poured upon them, followed by three healing breaths. The same procedure is done at the crown of the head. Then sobladas with tobacco smoke follow—as it is believed that it seals the blessing. Other communities use differing closing rituals.

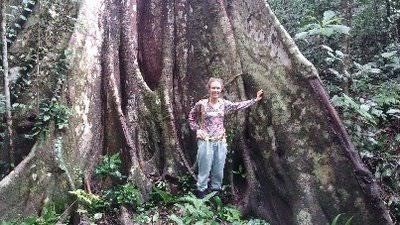

At Mayantuyaku people may be staying for two weeks, a month, or longer. The Maestro may prescribe specific master plants for ingesting two or three times a day. This is dependent upon physical and psychological conditions. For example, Tamamuri is considered to be a master plant. It is prepared as a decoction to extract the healing medicine. Bark from the tree is boiled in water, strained for drinking, or prepared in a final syrup. It is good for numerous conditions. (See http://www.rain-tree.com/tamamuri.htm#.WKjZwjsrI2x.)

Another master plant is the Camalonga seed of a plant of the Stychnos genus. It is carefully administered due to its inherent toxicity. It can be used to treat parasites, harmful bacterias, and other conditions. It is often used at Takiwasi, a center in Tarapota, Peru, established to treat cocaine and heroin addiction, as well as alcoholism. It is reportedly used for “newly admitted patients for ten days, combined with a sugar-free diet, in a program to detoxify certain unspecified energy disorders” (Beyer, 2010). These and other plant medicines are all part of preparation for ingesting the master teaching plant, Ayahuasca, to facilitate personal transformation and spiritual realization. Takiwasi was established by a French psychiatrist, Jacques Mabit, who works with local curanderos, psychotherapists, and others in an intense six-month to one-year+ program. As noted by the late Carl Jung, spiritual experience is often what an addict is seeking. Takiwasi offers this experience, supported by many integrative healing processes.

These are typical rituals found throughout the upper Amazon, although the form may differ from one group to another. For example, Kamsá healer, Taita Juan Bautista Agreda, of the Sibundoy Valley in Colombia, uses these remedies, as well as plant medicines found in Colombia. (The title Taita is a Colombian equivalent of master shaman.) He sometimes includes stinging nettle branches in a ceremony. This would be part of the “limpia” (cleansing ritual) done at the close of an Ayahuasca ceremony. (Generally, its male counterpart, a variation called Yagé, is used by the Colombian Taitas.) The goal of the stinging nettle branches being brushed on back, chest, arms, and neck is that of removing impurities blocking one’s life, and spiritual realization. This is done in ceremony, accompanied by song and music. Many people may have unhappily walked into stinging nettles at some point in their lives without unaware of its healing properties. I recommend researching the healing benefits of stinging nettles as you will be quite impressed in their wide-reaching medicinal impact.

Of note, Taita Juan, as well as the curandero Juan Flores of Mayantuyaku, have many students from a variety of cultures in training to lead spiritual ceremonies throughout the world (Anderson, Labate, & De Leon, 2013). Increasing numbers of people for Europe, Asia, UK, the Middle East, United States and other nations travel to regions of the upper Amazon to attend Ayahuasca ceremonies, hoping for healing or to receive life guidance. They are willing to vomit, perhaps have diarrhea, or whatever enables them to directly open to spiritual guidance. I was in Egypt last year for a women’s conference. A friend disclosed that an Ayahuasca ceremony had taken place on month before. I have learned that people are helping shamans obtain visas to guide ceremonies in many nations around the world. There are numerous books, documentaries, and YouTube videos on this so I won’t go into much detail. But I want to stress the point of this paper is to demonstrate that these ways of connecting with Nature directly through ingesting plants are a well-traveled path of Realization. Music is also included on this path.

Icaros

Plant medicine ceremonies generally include shamanic icaros, which are songs to the divine. Dr. Susana Bustos (2008) explains in her doctoral research at the California Institute for Integral Studies in collaboration with the Takiwasi Center in Peru that the songs have a power of their own. These songs are sung by the curanderos (healers) and vegetalistas (those who work with the master plants) throughout much of their work, as it is a way of communing with the plants. They are sung as plants are cut, cooked, and prepared, as well as throughout much of the ceremony. The belief is that the genie of the plants are attracted through the songs, and these spirits then give their blessings accordingly. Per Jacques Mabit, of the Takiwasi center, “when the diet

and training are correctly pursued, the songs end up inserted into the physical and energetic structure of the healer’s mind/body, from which the healer acquires the right resonance to sing them and activate their powers” (Bustos in Tindall, 2008, p. 261). It is believed that the most powerful icaros are those that come directly from the receptivity to the plant. This seems to correlate with the process that defines a Dance of Universal Peace to be more directly connected to the Stream. Icaros of many Amazonian cultures can be found with a google search, but these are examples from Mayantuyaku http://www.tonkiri.ca/icaros/

Increasing Responses to the Call

Increasing people are seeking a spirituality that includes the Living Guidance of Plants—the Messengers of Nature. The guidance is specific to the person’s life. Reports generally describe the guidance as coming from a presence attuned to, yet outside, the individual providing directions for development and healing within the individual.

Indigenous peoples have been doing such practices long before the traditionally-recognized world religions emerged. It is no surprise that so many people are seeking them out. In a short “film for action” titled ENOUGHNESS: Restoring balance to the economy in the most awesome way ever, it is noted that “indigenous peoples’ territory spans 24% of the earths land surface, but is home to 80% of its biodiversity. This is not a coincidence.” And, it’s not a coincidence that in this environmentally, and spiritually challenged time that people are seeking out and experiencing learning from indigenous ways.

The curanderos learned to listen to the plants. There are over 80,000 plant species in the Amazon. How did they know which plants would heal specific diseases? Out of such immense natural diversity, how did they know that “the leaves of a plant containing substances that inactivate an enzyme of the digestive tract, which would otherwise block the hallucinogenic effect” was needed for the effectiveness of the Ayahuasca brew? According to Jeremy Narby “It is as if they knew about the molecular properties of plants and the art of combining them, and when one asks them how they know such things, they say their knowledge comes directly from hallucinogenic plants” (1999, p. 22).

Nature offers us healing, as well as guidance, on physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual levels. At a time when the earth, our natural environment, is endangered, this is especially significant. It is also offering spiritual guidance to the many young people who have been disappointed in modern, often senseless, religious traditions. It offers yet another way of discovering the incredible diversity of the Divinity guiding all. Ziraat offers an attunement to Nature in recognition of all of Her gifts.

Copyright Sharon Mijares 2017. Email:

References:

Anderson, B.T., Labate, B.C. & De Leon, C.M. (2013). Healing with Yagé:

An interview with Taita Juan Bautista Agreda Chindoy. In Beatrice Labate Caiuby and Clancy Cavnar (Eds.) The therapeutic use of Ayahuasca. (pp. 197-215). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co.

Beyer, S.V. (2010). Singing to the plants: A guide to Mestizo Shamanism in

the upper Amazon. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Bustos, S. (2008). The healing power of the Icaros: A phenomenological

study of Ayahuasca experiences. Doctoral dissertation at the California Institute of Integral Studies.

d'Eaubonne, F. (1974). Le feminisme ou la mort. Paris: P. Horay.

ENOUGHNESS: Restoring balance to the economy in the most awesome way ever http://www.filmsforaction.org/watch/enoughness-restoring-balance-to-the-economy/

Mayantuyaku. http://www.mayantuyacu.com/las_plantas_maestras.html

McGrath, M. (1999). Pharmaceutical exploitation of the rainforests: Where do we draw the line? Downloaded 2/18/17, http://web.stanford.edu/class/e297c/trade_environment/children/hline.html

McKenna, D.J, Callaway, J.C. & Grob, C.S. (1998).The scientific investigation of ayahuasca: A review of past and current research. Heffter Review of Psychedelic Research,1:65-77. Also http://www.ayahuasca.com/science/the-scientific-investigation-of-ayahuasca-a-review-of-past-and-current-research/

Mijares, S. & Fotiou, E. (2015). Earth, gender and ceremony: Gender complementarity and sacred plants in Latin America. Journal of Transpersonal Research, Vol. 7(1). 57-68

Mijares, S., Rafea, A., Falik, R., & Schipper, J.E. (2007). The root of all evil: An exposition of prejudice, fundamentalism and gender imbalance. Exeter, UK: Imprint Academic.

Narby, J. (1999). The cosmic serpent: DNA and the origins of knowledge. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher.

Tindall, R. (2008). The jaguar that roams the mind: An Amazonian plant spirit odyssey. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press.